This interview was conducted by Alison Guss, producer from The History Channel for Drayton Hall’s interactive DVD tour of the landscape:

AG: Could you describe the construction and function of this building?

MW: Built in the 1790s by Charles Drayton, the second son of John Drayton and the second owner of Drayton Hall, the brick privy is Drayton Hall’s only remaining 18th century outbuilding. Changes over its 200+ year use illuminate different chapters of Drayton Hall’s story.

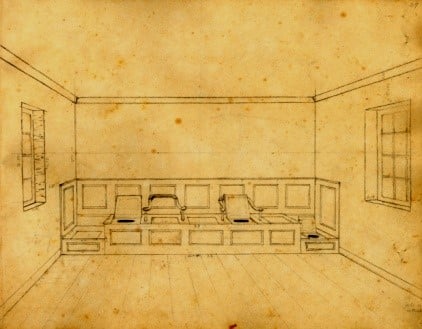

Originally, there were seven seats, as shown in the drawing of its interior of the 1840s. Originally, the structure had no fireplace or chimney, only windows. It was a cold bathroom!

Archaeologists found broken glassware, clay smoking pipes, chamber pots, and other artifacts because privies often served as trash bins. For example, if somebody was smoking a clay pipe in the bathroom, the pipe stems would end up out there. Broken glassware could be safely discarded into the hole.

As its drainage system demonstrates, this privy was advanced for its day and illustrates how Charles Drayton, who earned his M.D. from the University of Edinburgh, thought seriously about health and hygiene. At the northeast corner of today’s back wall, archaeologists found a brick box with an opening on one side that fed into the brick-lined drain along the back of the privy, about three feet deep. Above that drain line was a row of seven seats, two with arms, obviously for adults, and one at each end, lower in height for children.

MW: Like the detailing of the house and other outbuildings, the privy spoke to the status of the Drayton family. It compares easily to the best structures of this form in the Americas. This includes the five-seat, heated privy at Westover in Virginia, the fortified privy at Stewart’s Castle in Jamaica, and the finely constructed stone privy at Good Hope in Jamaica. Constructed of brick masonry with brick quoins at the corners, a molded water table, windows, stone steps, and even arms for two privy seats, its detailing was far beyond what would be expected for a building that served such a common purpose.

These details, however, are not the only feature that sets the Drayton privy apart. It is the functional component – the large drainage tunnel that leads from the structure. Most privies have ports directly below for drainage and/or cleaning. The drainage tunnel carried the effluent away and could even be flushed. This allowed the seated to avoid the unpleasantness of the effluent being held directly below. The Drayton Privy is yet another building that showed visitors the status of the family and the Charleston elite in 18th century society.”

Archaeologists excavate brick tunnel leading from Drayton Hall’s privy of the 1790s during the ownership of Charles Drayton. This tunnel connected to ditches, which led eventually to the Ashley River. Photo Credit: Drayton Hall Preservation Trust

Main image: A sketch of 1846 by Lewis Reeves Gibbes of the privy’s interior. Note the absence of a fireplace but the presence of creature comforts like wall panels, rather Mandarin-styled arm rests, and lower seats, presumably for children at each end. Below the seats is the drain line, described in the text. Credit: Drayton Hall Preservation Trust

George W. McDaniel, Ph.D., is President of McDaniel Consulting, LLC, a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and to its broader constituents. The company’s tag line, “Building Bridges through History,” is grounded in McDaniel’s personal beliefs and his experience in site management, preservation, education, board development, fundraising, and community outreach. Rather than using history to divide us, he strives to help organizations use history, especially local history, to enhance cross-cultural understanding and to support local museums, preservation, and education. Dr. McDaniel led volunteer efforts with Emanuel AME Church and historical organizations in Charleston to use historic preservation to enhance racial reconciliation and healing. McDaniel is also the Executive Director Emeritus of Drayton Hall, a historic site in Charleston, SC, owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He retired from Drayton Hall in 2015 after 25 years of distinguished service.

George W. McDaniel, Ph.D., is President of McDaniel Consulting, LLC, a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and to its broader constituents. The company’s tag line, “Building Bridges through History,” is grounded in McDaniel’s personal beliefs and his experience in site management, preservation, education, board development, fundraising, and community outreach. Rather than using history to divide us, he strives to help organizations use history, especially local history, to enhance cross-cultural understanding and to support local museums, preservation, and education. Dr. McDaniel led volunteer efforts with Emanuel AME Church and historical organizations in Charleston to use historic preservation to enhance racial reconciliation and healing. McDaniel is also the Executive Director Emeritus of Drayton Hall, a historic site in Charleston, SC, owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He retired from Drayton Hall in 2015 after 25 years of distinguished service.

A frequent writer, speaker, and facilitator about such issues, he can be reached at gmcdaniel4444@gmail.com or through his website at www.mcdanielconsulting.net.

All images courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.

McDaniel Consulting LLC is a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and its broader constituents.

McDaniel Consulting LLC is a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and its broader constituents.