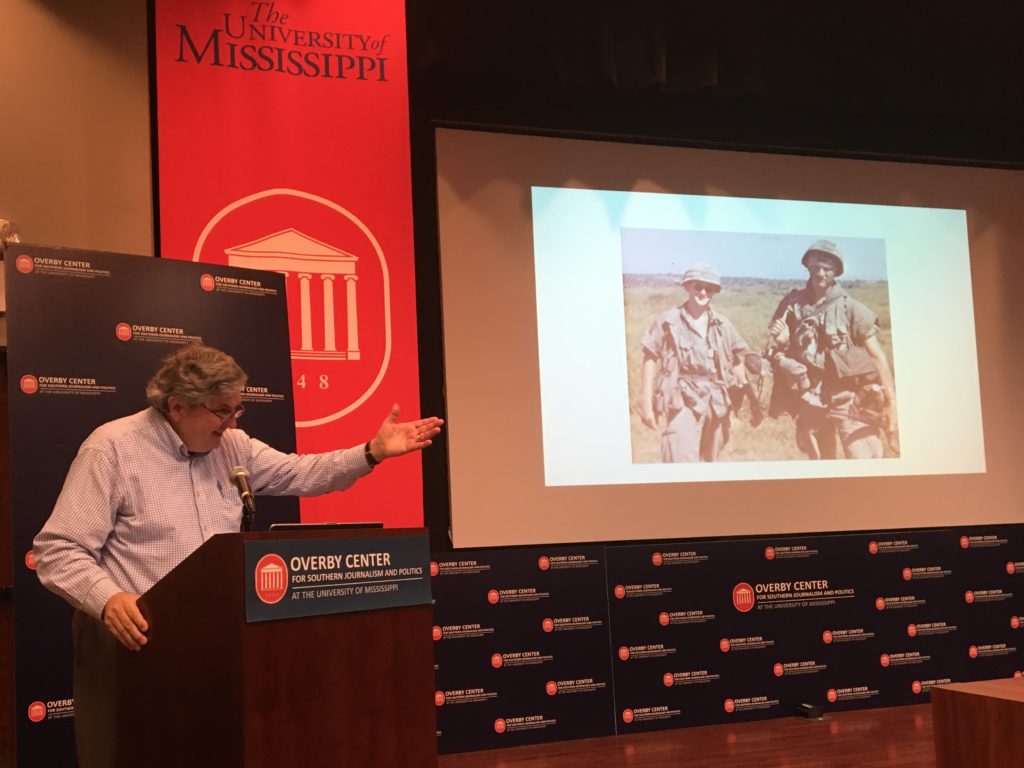

Opening Up History & Healing Wounds: Choosing a Future for Confederate Memorials

University of Mississippi – October 3, 2017

What do Confederate Memorials mean and what do we do with them? These are questions that have us struggling to find common ground. The University of Mississippi invited me to address faculty and students on this topic and offer my perspective as a lifelong public historian and as part of the sub-committee helping to commemorate the “Emmanuel Nine” tragedy at Mother Emmanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, SC.

While I hope you’ll watch the video of the entire presentation (below), I’ve excerpted a section from my original draft that will provide you with a sense of my perspective and how I arrived at what I believe to be a workable approach to these difficult questions. I should note that after my presentation and discussions at the University of Mississippi, I will be making additional edits. Also, I welcome feedback from all readers, for this is due to be published by the American Association for State and Local history this winter in its book on memorials.

I was recently watching The Vietnam War on PBS, a film produced by Ken Burns and Lyn Novick. They seek to present multiple points of view. I certainly have mine, and that is roughly divided into three parts: before I went to Vietnam; while I was in combat there; and when I returned home and reflected upon my experiences. The latter, in fact, has changed over time, as the war has grown more distant, and the feelings less raw.

I am sure the film has generated mixed feelings among Americans across the nation — the veterans, their families, those who lost a loved one, those who demonstrated against the war, and those, perhaps the majority, who went on living their lives and building a career or a family because the war was someone else’s and “over there.” And for millions more, born after the war, it may seem like “ancient history.” For the Vietnamese who refugeed here and for those that remained, the war was seen quite differently. It was not “over there,” or someone else’s, but rather something that happened to their home and community, to them personally, whether they had wished it or not.

These different perspectives may inform us about war memorials in general, and about Confederate memorials in particular. Recently there have been attempts to reduce the memorials to a single interpretation. We are familiar with them and the disputes. Recently strong has been the argument we have heard that they are, and have been, deeply offensive to many Americans for a long time, especially to African Americans. To many white Southerners, they have become an essential part of the landscape of county seats and state capitals, while to still others, they have been barely noticed, part of a history they don’t know or much care about. Sheffield Hale, president and CEO of the Atlanta History Center, recently wrote a well-reasoned essay in History News, the publication of the American Association for State and Local History, about the Center’s work in finding and promoting solutions and in using the memorials and their lessons to civic advantage. He urged research and discussion, and their work has resulted in positive results in Atlanta, Oxford, MS, and elsewhere. However, after the hateful violence and killing in Charlottesville, civil discussion has become hard pressed, and the argument that such monuments were erected solely as part of the effort to re-exert and solidify the triumph of white supremacy after the Civil War has gained much higher ascendancy…

…I would suggest that the Vietnam Memorial may be of help, for it tells us that monuments mean more than ideology and prompts us to look at them from different perspectives. On the one hand, the Memorial is a monument to what many have concluded was a “mistake” and clearly a defeat. On the other hand, with my being a Vietnam veteran, the Memorial meant that, but more. It was both personal and collective, for when I came home, my world was pretty shattered. While it may have seemed normal on the outside, it wasn’t normal to me on the inside, especially at night. I had been set apart. For that reason, more than a decade later, I went to Washington by myself for the dedication of the Wall. I didn’t know a soul. I was standing on the sidewalk of Constitution Avenue watching a “parade” of vets walking past, all in civilian clothes, when I saw a banner, “First Infantry Division, Big Red One.” I walked out and joined the crowd, and asked guys what unit they had been with and when. As they were welcoming me and I was telling them, “First of the 18th, Alpha Company, 69-70,” a guy yelled, “Mac.” It was my lieutenant, and we embraced on the spot. He hadn’t known if I had gotten home alive, or I him. When we ended up at the Memorial, we heard speeches, but what was more special was that my memories of Vietnam were given a physical reality by the Memorial. I could see it and touch it. Guys I knew were named on it. It was a deeply private and personal connection…

When I returned from Washington, I set about trying to contact the family of a friend in my platoon, Claude Giles, who had been killed on a mission by “friendly fire.” He was from Toccoa, GA. I had been reticent to call his widow or mother when I returned in 1970 because I didn’t know what the Army had told his family about his death. Perhaps they’d been told he’d died a hero’s death and not as a result of mistaken communications. During the dry season we had been sent into open rice fields and set up nighttime ambushes behind low dikes to protect a village from Viet Cong slipping in for food, money, or worse. Located in a position not far from mine, he’d been killed by one of our snipers in another ambush position, who was using a starlight scope and hadn’t been informed of Claude’s nighttime location. He put two rounds in his chest. When I did telephone Claude’s mother, she was so glad to hear from me and learn of my visit to the Memorial. She had been told the truth, but what she wanted to hear again and again was that Claude’s name is on the Wall. I assured her that it was, and she wept. Her son had been remembered.

I recount this because when these Confederate memorials were going up from the 1880s to the 1920s or even later, Confederate soldiers would still have been alive, though in diminishing numbers, along with parents and widows in earlier years, brothers and sisters, children, grandchildren, and friends. While the monument may have been to Robert E. Lee or Jackson, or to soldiers in general, white supremacy was certainly a value they adhered to, but also to many the monument may have meant their lost ones had not been forgotten. They had not died in a “mistake.” There was pride in their combat, in what they had gone through. They did not have the photographs, videos, audio-recordings, or even letters to remember them by, the very things we take for granted today. For them, the monument may have also stood for the wounded, physically and mentally, many of whom, given the carnage of that war, had been scarred in ways we can hardly understand since so much of it went undocumented. For veterans especially, the monument may have stood not just for the glories, but the gore they saw on the battlefield and in the hospitals, things which the civilians around them could not imagine. What may have touched them was not so much the speeches, but the memory of friendships. While politicians may have talked of the Lost Cause and our “glorious dead,” they would have seen the reality of the latter, which was not pretty. The memorial may have helped them feel more connected to both the dead and the living. And like Mrs. Giles, to her son and to the future.

While I understand the anger that Confederate memorials can generate and the rationale that they represent the triumph of white supremacy, I also think that monuments may mean many things, and we reduce them to only one thing at our peril. As a result, I think we should proceed not by way of a “take it or leave it” choice, but look for “both/and” solutions and use them as teachable moments and capitalize on this heightened concern for history. Like we today, the people of that time did not act out of only one motive. White supremacy was there, of course, and an awful force, but to conclude that was the one and only motive is to be reductionist. We don’t credit those people with the latitude we give ourselves…

…A war is never over. It is not over for us Vietnam vets, though it’s been about 50 years. It’s not over for the Civil War, though it’s been 150. The legacy continues to shape our society, politics, education, and race relations. While we’ve made progress and deserve to be proud of that, what we haven’t done enough of is to come together — to break bread together, to worship together, and just talk with one another, sharing our fears and aspirations, not so much to debate or persuade one another of the rightness of our position, but to develop mutual understanding, empathy, and tolerance. If that becomes our goal, the question then becomes: How can we use these monuments to help us get there?…

Photos above (1) With University of Mississippi faculty, including Chancellor Jeffrey and Sharon Vitter on either side of me. (2) With Chuck Ross, head of the history department. (3) Part of my presentation: friends in my platoon in Vietnam, Claude Giles and Steve McCool. (4) With my son George who is a student at the university.

Click below to watch the presentation:

George W. McDaniel, Ph.D., is President of McDaniel Consulting, LLC, a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and to its broader constituents. The company’s tag line, “Building Bridges through History,” is grounded in McDaniel’s personal beliefs and his experience in site management, preservation, education, board development, fundraising, and community outreach. Rather than using history to divide us, he strives to help organizations use history, especially local history, to enhance cross-cultural understanding and to support local museums, preservation, and education. Dr. McDaniel recently led volunteer efforts with Emanuel AME Church and historical organizations in Charleston to use historic preservation to enhance racial reconciliation and healing.

George W. McDaniel, Ph.D., is President of McDaniel Consulting, LLC, a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and to its broader constituents. The company’s tag line, “Building Bridges through History,” is grounded in McDaniel’s personal beliefs and his experience in site management, preservation, education, board development, fundraising, and community outreach. Rather than using history to divide us, he strives to help organizations use history, especially local history, to enhance cross-cultural understanding and to support local museums, preservation, and education. Dr. McDaniel recently led volunteer efforts with Emanuel AME Church and historical organizations in Charleston to use historic preservation to enhance racial reconciliation and healing.

McDaniel is also the Executive Director Emeritus of Drayton Hall, a historic site in Charleston, SC, owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He retired from Drayton Hall in 2015 after 25 years of distinguished service.

Header Image – Photo Credit: University of Mississippi website home page, October 2017

McDaniel Consulting LLC is a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and its broader constituents.

McDaniel Consulting LLC is a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and its broader constituents.

George,

Beautifully written. Your analogies, drawn from personal experience, helped create a space in my thoughts for more than a reductionist view, so thank you.

Thank you for your service in Vietnam and for talking about it in such a meaningful way.

Many thanks, Fielding, your comments mean a lot and give encouragement, which is needed in times like these. I also appreciate your comments about my service in Vietnam, an experience much still a part of me.