In 1968, I lived in the upcountry of Togo, West Africa for about 6 months before being drafted into the Army, about which I’ve written. Though I’ve written about life in Siou and Niamtougou, what about hygiene? Since that was 50 years ago, I’m sure things have improved, just as it has elsewhere. It’s not something talked about and something we Americans take for granted, but hygiene is different in different parts of the world. It shapes life.

At that time in1968 in the upcountry of Togo, there was no running water in underground pipes to and from your residence. No wells supplying year-round water. How did that affect your everyday life? Please think about that the next time you: drink water; add water to a drink; add water to cook something; brush your teeth or wash dishes; flush a toilet; water your lawn or your garden; wash clothes; turn on your sink to clean; the list could go on, but you get the idea.

Where I lived in Niamtougou, Togo, if you wanted water, you had to get it yourself. At the house I rented, there was a well, dug by hand, about 10 feet deep, but during the dry season, the water table sank since it was on a slight hilltop, so the well went dry. I’d stored water in rain barrels that caught water cascading off my tin roof during the rainy season, but water gradually became all the more precious. You didn’t bathe or wash clothes as frequently, or cook with as much water. Think of your life without water anytime you want, and imagine how you might live with clean water in short supply. That was how we lived our lives in the dry season.

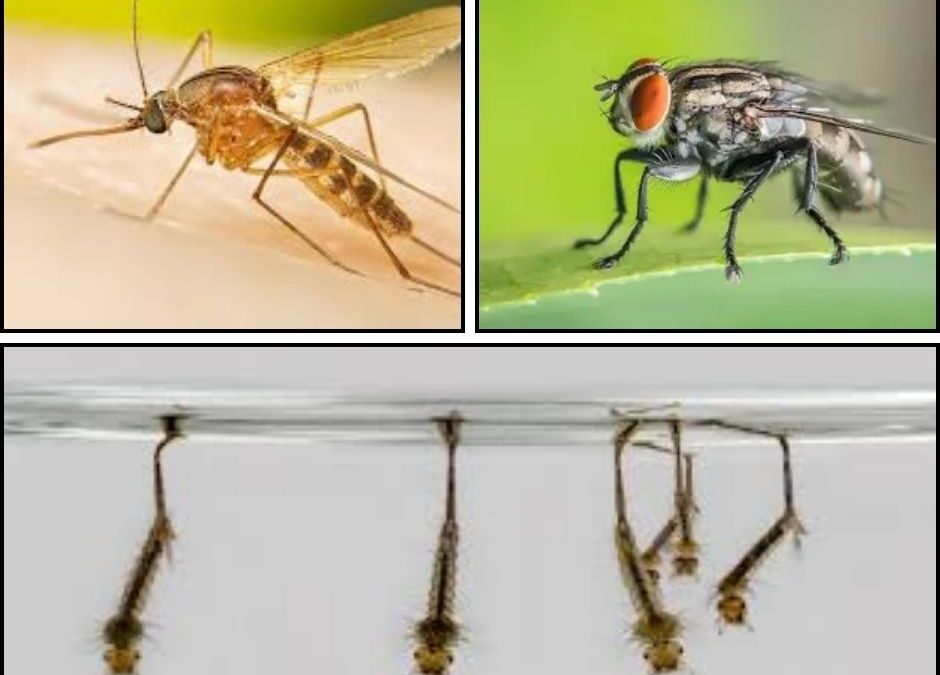

To clean the drinking water, we could add pills that the Peace Corps had given us, but the pills gave us diarrhea, so after a few times, we didn’t use them. In the rain barrels, mosquitoes would lay eggs so after a short while, you’d see larvae swimming around in the water (see photo below). At first, you didn’t like it, but after “seasoning,” we got used to it.

We used a tall ceramic cylinder, like a coffee urn but taller, to clean our water of larvae and dust, after which you were supposed to boil it. Boiling became too troublesome, so we just cleaned the pumice stone of larvae and dust, and let it rip. Often we’d dip out water free of larvae and use that. Diarrhea was common, whether from water, the food, the mosquitoes, the flies — you didn’t know, so you just lived with it.

Often it’d pass. When first in-country, I got sick and couldn’t keep anything in at both ends. I became weaker and weaker. When I went out for Peace Corps training in construction or agriculture, I’d work for a while and then excuse myself to go heave. After two weeks or so, I became so weak I had to stay in bed. My Peace Corps friends took to calling me “Gandhi.”

I was taken to a Peace Corps nurse in another village. En route, I heaved. At her house I felt fine, accepted a Coca-Cola from her (Cokes were ubiquitous), then promptly excused myself, and there being no running water, stepped outside her front door and heaved the Coca Cola in her bushes.

The nurse said a mosquito-borne illness was infecting people, so if I didn’t get better, I’d have to go to the hospital in Lome, the capital city, about a day’s drive — 250 miles. I got better. Maybe I got “seasoned.”

One Peace Corps Volunteer in the Ivory Coast, a friend of mine, had it so bad she had to go to a hospital in Europe due to worms in her digestive tract, but that was rare. It took her several years to get rid of them, since the worms laid eggs that burrowed into her tissue, lay dormant, then sprang forth. She had them when she returned to the States, and her doctor in Boston didn’t believe her at first.

You simply got used to it. About once a month, you’d have it and then it’d pass, and you’d be fine, and then again. It was common. You knew that every rural Peace Corps Volunteer, whether male or female, had it, but except among close friends, it was not something we talked about.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

George W. McDaniel, PhD, is the President of McDaniel Consulting, LLC, a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and to its broader constituents. For 25 years, he served as the Executive Director of Drayton Hall, a historic site in Charleston, SC. A native of Atlanta, he earned a BA from Sewanee, a MAT (history) from Brown University, and PhD (history) from Duke. Interspersed through those years were travels to many places — Europe, Africa, Vietnam — where he saw peace and war and learned by experience about cultural differences and commonalities. For 40 years, he built a career working in education and history museums, beginning with the Smithsonian Institution, and earning awards at the local, state, and national levels.

“Building Bridges through History”

The company’s tagline is grounded in McDaniel’s personal beliefs and his professional experience. Services address site management, preservation, education, board development, fundraising, community outreach, and more.

Rather than using history to divide us, McDaniel helps organizations use history, especially local history, to enhance cross-cultural understanding and to support local museums, preservation, and education.

Turning Beliefs into Actions

Dr. McDaniel led volunteer efforts with Emanuel AME Church and historical organizations in Charleston to use historic preservation to enhance racial reconciliation and healing.

A frequent writer, speaker, and facilitator, reach him at gmcdaniel4444@gmail.com or through his website www.mcdanielconsulting.net.

Images courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.

McDaniel Consulting LLC is a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and its broader constituents.

McDaniel Consulting LLC is a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and its broader constituents.