Craig M. Bennett Jr., PE, (shown above), is the president of Bennett Preservation Engineering, PC, in Charleston. A native Charlestonian, he is a structural engineer, specializing in historic preservation.

GWM: How would you characterize Drayton Hall’s masonry construction?

CMB: Drayton Hall’s masonry is beautiful. In this area, masonry was generally pretty good up until about 1840, and Drayton Hall is a perfect example of that. In 1840, things thinned out a fair bit, because people started using a different bond, making the buildings built after 1840 nowhere near as well built as those built before.

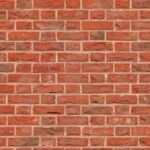

Over time, the wythes, or vertical sections of a brick, will delaminate — that is, they separate from one another – or they may crack or crumble due to weather, rising damp, or age. All of this weakens the wall. However, alternating bricks in orientation, as in the Flemish bond you see at Drayton Hall (above bottom row, far right), serves as a kind of glue, locking the wythes of brick together. Also, for those bricks whose headers are exposed to the weather, their stretchers are protected. The result: strength and beauty.

Above: Clear close-up of Flemish bond masonry, not at Drayton Hall, but illustrating how the header of the brick alternates with the stretcher. This gives strength to the wall, and the eye discerns differences in orientation so the brick is not seen as monotonous.

Above: Flemish bond masonry, as used at Drayton Hall, revealing how the bricks’ orientation strengthens the masonry by locking the bricks in place. There is no one plane by which the wall can shear or split.

A frequent writer, speaker, and facilitator about such issues, he can be reached at gmcdaniel4444@gmail.com or through his website at www.mcdanielconsulting.net.

All images courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.