Lovett Community Summit on Global Perspectives

April 23rd 2018

The Lovett “Community Summit on Global Perspectives” is about engaging with and learning about multiple perspectives, life experiences, and cultures. Given that cross-cultural understanding occurs most richly when people meet face to face, the day is dedicated to allowing students and faculty members to discuss a multitude of topics through the sharing of their own experiences.

The goals of the Lovett Global Summit are to:

- Recognize the many factors that influence who people are and how they communicate.

- Investigate and appreciate cultural differences as well as similarities, looking beneath the surface of stereotypes.

- Reflect on one’s personal experiences across cultures to re-evaluate personal feelings, thoughts, perceptions, and reactions.

My personal, much-abbreviated story of gaining a global perspective began with growing up in Atlanta and going to the Lovett School where I first learned the value of being adventurous, of traveling, exploring, keeping an open mind, and asking questions. Later, I would spend my junior year in college in Paris and then travel across Europe, returning to teach at Lovett at the ripe old age of 22. Two years later I would join the Peace Corps in Togo, West Africa, then fight with the First Infantry in Vietnam. After returning home, I built a life, grounded in all that I had learned. It was because of these experiences that I was asked to speak at Lovett’s 2018 Global Summit and to teach two classes on the following days using points and concepts from the Global Summit.

With the Summit’s goals in mind, and knowing my lectures would each be slightly over an hour in length, I used my museum education experience to create what I thought would be some good interactive approaches to student engagement while keeping in mind the old saying that “when the butt gets tired, the mind gets numb.”

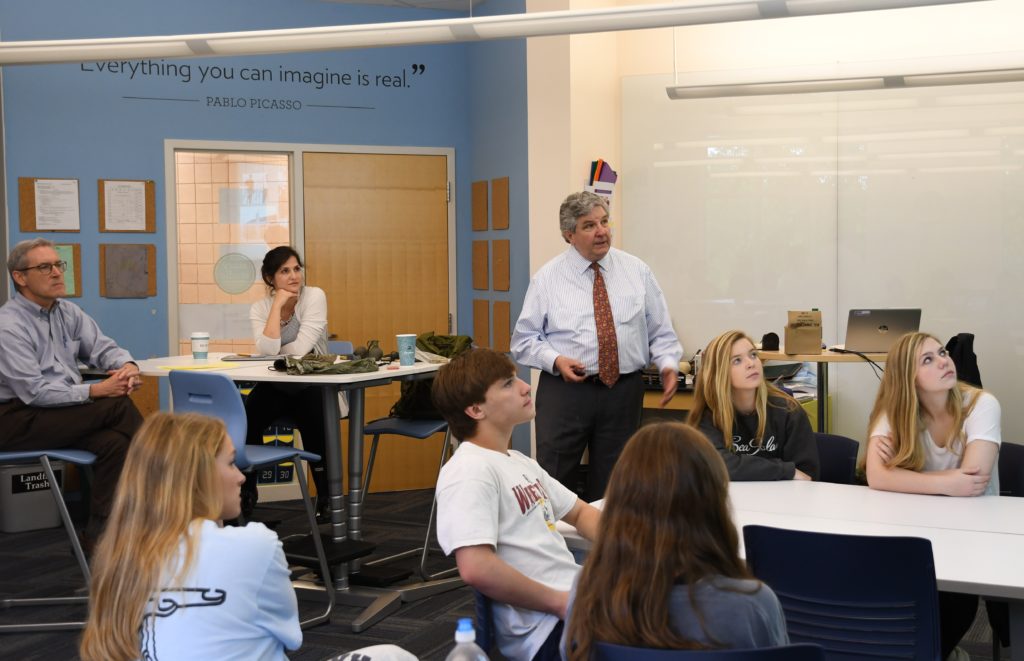

Global Summit, April 23 – The Local & The Global: The Shaping of a Lovett Alumnus

How do you encourage high school students to step out of their bubble and appreciate different cultures? To have an open mind? My approach was to describe my trajectory from the local to the global and back again—with concrete examples of how it changed me for the better, made be more aware of the world and people around me, and strengthened my empathy for others.

In taking this approach, I encouraged students to look beyond their local horizons and ask questions of the world. My goal for the brief time that we would be together was to guide them to think and act with empathy—to learn to walk in someone else’s shoes—as responsible global citizens in an increasingly diverse landscape. How to do that? By moving beyond their local environment, by popping the bubble that they live in and letting the fresh air in. I also made the point that it’s not a choice between the two, it’s not either/or, it’s both local and global because we need both continuity and change for personal growth.

Describing my trajectory from the local to the global and back again.

Demonstrating teaching through art, a global perspective.

I spoke about my first global experience beginning with how my teachers at Lovett had challenged and inspired me. Thanks to them, I would go on to learn French at Sewanee and study abroad as part of the Junior Year in France Program offered by Sweet Briar College. I traveled to New York to take a ship to Paris; while in NY I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see the great works—an experience that impacted me in ways I couldn’t begin to imagine then.

It would take six days to travel by ship to Europe, but college students will always find ways to have fun.

Immersed in European culture, we spoke French in and out of the classroom and visited historic sites that inspired me to work in historic preservation.

We arrived in Paris, and though I could read, write, and understand conversation well, I was embarrassed by my accent, which I knew was awful. I worked on my French with my French family, mimicking how they spoke and focusing on pronunciation—in other words, I was an empathetic listener, focusing on them, not me. By the end of the year I was fluent in French, my accent very good.

As students, we were totally immersed in the French culture—all classes, essays, and exams were in French. The courses opened our minds to new realms—we studied Moliere and visited Versailles where he had performed; we attended plays at La Comedie Francaise in Paris and studied art history at the Louvre Museum. We were introduced to a new way of learning: we were taught in a holistic manner, illuminating the connections among art, architecture, music, history, people, culture, food, and more. We met people different from us. We learned to speak their own language and did not expect them to speak English.

Me as a young teacher at Lovett. I turned 20 in Paris and would return to Lovett after college graduation, bringing my global experience with me to teach both European history and French, incorporating lessons that I didn’t have as a student.

My lecture at the Global Summit ended with some good Q&A, after which I felt the need to leave the students with two important thoughts: that exploring new places is not denying your home, and asking new questions is not being anti-religious because the opposite of faith is not doubt, but certainty. In the words of scientist Stephen Hawking, “The greatest enemy is not ignorance, but the illusion of knowledge.”

I then had the pleasure of teaching classes on the following days using points and concepts that would reinforce the goals of the Summit.

April 24 – The Things They Carried – American Studies

How do you teach high-school students about a war that took place 50 years ago in ways that engage them mentally and physically without sanitizing war? What lessons do you teach?

As preparation, teachers had asked the students (high-school juniors) to read an excerpt from the book, The Things They Carried. Published in 1990, it is a collection of short stories about a platoon of American soldiers fighting on the ground in the Vietnam War in 1968-69. Author Tim O’Brien, an American novelist, based it on his experiences as a soldier in the 23rd Infantry Division.

For the interactive component of my lecture, I began with some simple exercises to help explain what it was like to be a soldier and how we stayed alive. I demonstrated the need for mastering life-saving techniques, like detecting the different sounds of gunfire and what they meant, and the value of mutual trust, like knowing your fellow soldiers’ locations at any given time. Why? Because the lack of such knowledge and failure to follow strict field discipline could get you and your buddies killed.

Vietnam – Fall 1969. Mike Platoon, Alpha Company, 1st Infantry Division. What was I carrying? I was travelling light, possibly the dry season. Mission: one-day patrol or reconnaissance around village since canteen not visible. About 70-80 lbs. of gear: ammo, frags on belt, radio in my ruck sack, plus more ammo, flares, and Claymore mines. My side pockets were full, too.

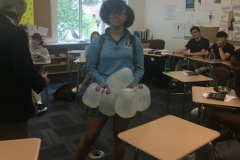

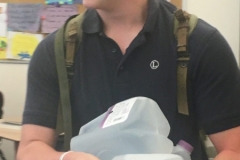

I then used actual artifacts from my service in Vietnam to discuss the very objects that they had just read about—I passed some around and we had a good exchange about their purpose and importance. Some students volunteered to experience what it was like to carry 70-to-80 pounds while out on patrol. Some studied my dog tags with interest and were surprised to see them encased in plastic and on a heavy cord rather than loose and attached to a metal chain like in the movies. I explained that the sound of jingling tags or a bright point of light reflected off their metal surface could give your location away to the enemy and get you killed. I talked about what we were fighting for—democracy and anti-communism—but to be honest, I stressed that most soldiers—many of them just a few years older than the students—were focused hard on two things: staying alive and going home.

The real turning point in the lecture came when I described my own close call. I was on patrol with a fellow soldier to protect a village from the Viet Cong. He was walking point and I was right behind him, but was caught up in some brambles—I asked him to wait a minute. In the next moment, I was blown up in the air by a blast from a booby-trapped mortar round—I landed on my back and was wounded in the face. I remembered my training to stay where you are, but I had to get to my buddy who was badly hurt—both of his legs had been snapped like toothpicks. I shot him with morphine and he was medevaced out of there while I chose to stay with my unit. At base camp, they left the shrapnel in my face and the bone has since grown around it. Surgery saved my buddy’s legs, but he could no longer serve and was sent back to his home in New Jersey. Had I not been delayed and been even one or two steps closer to the blast, I could have met a similar fate and, perhaps, not have been so lucky. This story more than any other helped to drive home the fact to young students that war is real.

By communicating my real-life experience in Vietnam to students during the school’s Global Summit, it is my hope that these examples will help them open their minds and examine their own thoughts, perceptions and misconceptions about the realities of war and sacrifice, beyond mere abstractions.

April 25 – Empathy Builds Bridges, Togo, West Africa – Second-Year French Class

How do you interest high-school students in a place and people they may think they have little in common with? How do you open their minds? How do you get them to care?

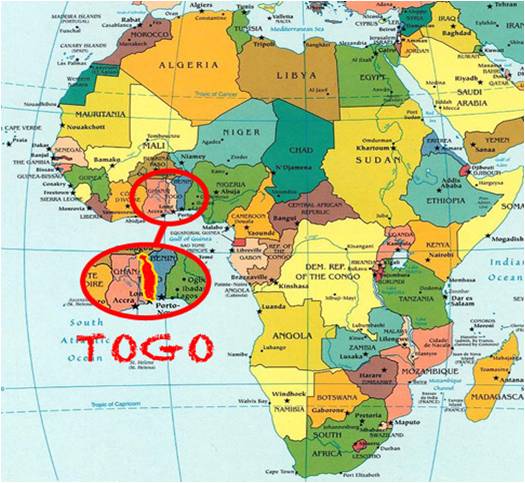

In 1968, I left teaching to join the U.S. Peace Corps to serve in Togo, West Africa. I was around 24 at the time. I had lived in France for a year as a student and I had traveled throughout Europe meeting many different people and experiencing different cultures. Togo, our group of young idealists quickly learned, was a very different reality and any assumptions that we may have brought from America did not apply.

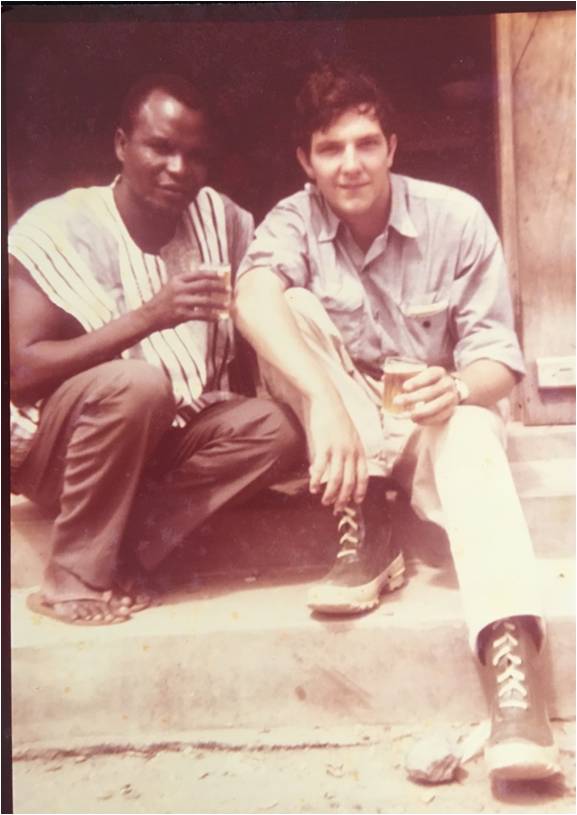

Togo was rural and agricultural and its people led a traditional village life. There were few to no modern amenities: no telephone, telegraph, running water, or electricity. The climate was tropical and there were two seasons: rainy and dry—not the four seasons that we know—and while the countryside was lovely, the soil was not fertile. All the time we were there, we were to live like the villagers, respect the local circumstances, and get to know and value their culture. The natives spoke forty-plus languages, so while I spoke French fluently, we all had to work on learning essential words and phrases in as many of the other languages as we could in order to make friends, gain their trust, and provide the needed assistance. Our work was very much hands-on and we knew that if we were successful, we could have a positive and lasting impact on people’s lives. In exchange for meeting those challenges, we came away with lifelong lessons. For me, it was an expansion of my global perspective as I came to a deeper understanding that we all share the same values—those of honesty, hard work, family, religion, and community life. I came to respect our common humanity.

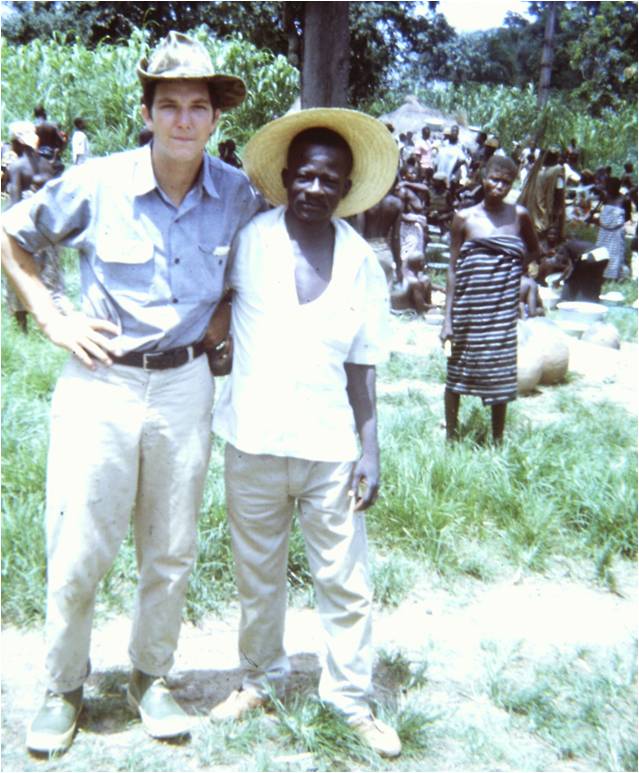

With Ta Ta Norbert, my Togolese counterpart

With Monsieur Daniel, local doctor (Petit Fetisheur) (Witch Doctor) (Priest Doctor)

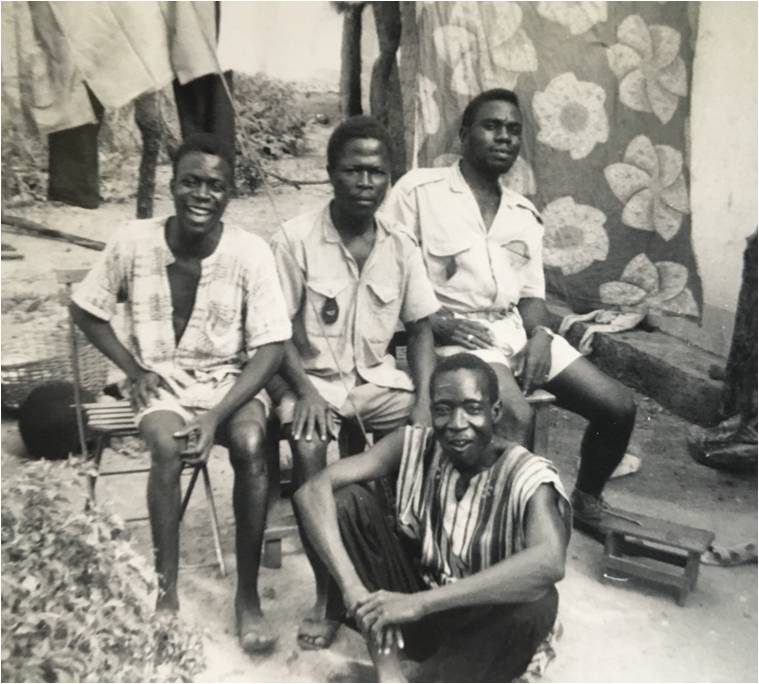

More Togo friends—with them, I learned about the local village and culture and took part in social gatherings.

I explained all of this to the class in French; as second-year students they could understand more than they could speak. Interested in finding out just how much they had absorbed—for example, did they grasp the key concept of empathy?—I asked them to report on what they learned and I look forward to reading their comments.

The Circle Unbroken – A Postcript to my Experience at the Global Summit

In being asked to reflect on the earliest years that helped to shape my global perspective, and keeping the goals of the Summit foremost in my mind as I did so, I recognized that by continually honing my skills in empathic learning—in focusing on each individual and using the understanding that I gained to help guide my actions—that I not only became a better person, teacher, and historian, but that I was ultimately inspired to pursue my present-day mission to help others realize the positive impact of cross-cultural understanding. I thank the Lovett School for the opportunity and am grateful to have been part of this important discussion.

George W. McDaniel, Ph.D., is President of McDaniel Consulting, LLC, a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and to its broader constituents. The company’s tag line, “Building Bridges through History,” is grounded in McDaniel’s personal beliefs and his experience in site management, preservation, education, board development, fundraising, and community outreach. Rather than using history to divide us, he strives to help organizations use history, especially local history, to enhance cross-cultural understanding and to support local museums, preservation, and education. Dr. McDaniel recently led volunteer efforts with Emanuel AME Church and historical organizations in Charleston to use historic preservation to enhance racial reconciliation and healing. McDaniel is also the Executive Director Emeritus of Drayton Hall, a historic site in Charleston, SC, owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He retired from Drayton Hall in 2015 after 25 years of distinguished service.

George W. McDaniel, Ph.D., is President of McDaniel Consulting, LLC, a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and to its broader constituents. The company’s tag line, “Building Bridges through History,” is grounded in McDaniel’s personal beliefs and his experience in site management, preservation, education, board development, fundraising, and community outreach. Rather than using history to divide us, he strives to help organizations use history, especially local history, to enhance cross-cultural understanding and to support local museums, preservation, and education. Dr. McDaniel recently led volunteer efforts with Emanuel AME Church and historical organizations in Charleston to use historic preservation to enhance racial reconciliation and healing. McDaniel is also the Executive Director Emeritus of Drayton Hall, a historic site in Charleston, SC, owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He retired from Drayton Hall in 2015 after 25 years of distinguished service.

A frequent writer, speaker, and facilitator about such issues, he can be reached at gmcdaniel4444@gmail.com or through his website at www.mcdanielconsulting.net.

Header Image: Graphic for the Lovett Schools Global Summit, courtesy of The Lovett School

All classroom images by Lovett School photographer Perry McIntyre. Vietnam images from the author’s archives.

McDaniel Consulting LLC is a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and its broader constituents.

McDaniel Consulting LLC is a strategy firm that helps organizations use history to build bridges within itself and its broader constituents.